Have you heard the news? Open-world games are dead. DEAAAAD!

Or so claims popular Youtuber and video game journalist Yahtzee in his semi-tongue-in-cheek video for The Escapist, titled “The Open World Is Dead, Sorry”. Yes, he admits, AAA publishers are still making open-world games, and yes, they are planning to release more of them in the coming years. But, their entertainment value has worn off, and eventually, their popularity will wane too. The core of his argument is that open-world games have become too stale, too safe, to be engaging, which means that as a genre (or video game “type,” if you prefer), they are destined to fade into obscurity.

According to Yahtzee, this staleness derives from how open-world games tell their stories. The narrative focus is usually always on the worlds themselves rather than characters. Typically, the world is either corrupted or occupied by some malicious force, which the player then has to eradicate. They accomplish this by exploring the map and engaging with its various activities, such as clearing enemy camps, completing missions and so forth. Titles like Ghost of Tsushima, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild, Far Cry 6 and Assassin’s Creed Valhalla all arguably follow this storytelling/gameplay template. These plots are overly simplistic and tired, Yahtzee argues. He adds that there are certainly exceptions to this rule, like Red Dead Redemption 2 and Grand Theft Auto 5, which do focus on characters. However, as a trade-off, their story missions often restrict the player’s use of the open world, to keep the narrative on track (“almost as though the open world is a hinderance to the narrative,” as he puts it).

To distract players from this formulaicness, AAA publishers have opted to make their games bigger and bloatier, which has led to more intensive development cycles, both in terms of cost and human effort. Yahtzee concludes that we’re finally reaching the limit as to how big and bloated these games can be, which may make them unfeasible in the near future.

While I agree with him that AAA open-world games have become too big, bloated and stale, and shouldn’t be any bigger, I do think they can improve. As Yahtzee himself admits, indies like The Outer Wilds have presented us with some of the most carefully constructed open worlds to date, so I don’t see why AAA publishers can’t follow suit. They have the money and talent, after all.

With that in mind, here’s what I think AAA publishers can do to truly spice up the open-world formula:

1. Divide the Map into Smaller, More Varied Regions/Biomes

Though Assassin’s Creed Valhalla can at times feel like a long and repetitive slog – particularly if you’re a completionist – it does guide the player through its open world in a somewhat unique way. The game is set in medieval England – the entirety of England, in fact, not just a single city or region. However, despite its overwhelming size, you don’t get to explore it all at once. That’s because the map is broken up into several small regions – or biomes, if you will – with the story encouraging you to visit them one at a time instead of hopping back and forth between them, like in the previous Assassin’s Creed entries. Basically, you visit a region, do all the necessary quests within it, then move on to the next one, never to return (unless you want to).

The map of England in Assassin’s Creed Valhalla.

The idea of regions/biomes isn’t anything new, of course, since even games as old as Grand Theft Auto 3 had them. The difference is that in Valhalla, regions are both plentiful and small. There’s over a dozen of them in fact, whereas in Grand Theft Auto 3, there are only three. I bring this up because to this day, most open-world games have about three to four regions/biomes as opposed to multitudes of smaller ones, like in Valhalla.

Having smaller regions/biomes would reduce the time it takes to travel around a vast map in search of content and get them to their objective sooner. I would compare these tiny-ish regions/biomes to the open-ended levels of the original Crysis game, in which travel time is present, giving the impression of a large location, but is never long enough to become boring, as the next story bit or action set piece is just around the corner. So, think something similar, but maybe slightly bigger and connected seamlessly to a larger world, like in Valhalla or Grand Theft Auto.

I would add that these small regions/biomes should be visually distinct from each other, so that the player knowns, beyond any doubt, that they are in a new area. The same applies to gameplay activities, such as quests, which should be unique enough to avoid the perpetual sense of déjà vu open-world games like Valhalla tend to induce. After all, most of Valhalla’s England is but a collection of green hills, forests, rivers and forts, and its quests are all concerned with winning over kingdoms and little else, which can get boring and repetitive after numerous hours of play.

It would be neat if you could over the course of a single game, visit and explore a place like this:

Then maybe a place like this:

Then a place like this:

A place this:

And finally, a place like this:

Again, they don’t have to be enormous – just large enough to feel as though you’re not on a linear path, which I think is the biggest appeal of the open world.

2. Make Each Biome/Region Affect Gameplay in a Significant Way

To further avoid the feeling of repetition, each biome/region needs to bring something unique to the table in terms of gameplay, the same way levels/stages do in traditional, more linear games.

My favorite example of this is Half-Life 2, which admittedly is an old game by now, but there’s a reason people still talk about it. Each level in this game feels unique, either because of the enemies you face in it, the way you traverse it or its overall appearance. In one level, you may be stuck in an abandoned town, fighting for your life against a swarm of zombies, and in another, you may be driving a vehicle across a deserted landscape while being chased by an alien gunship.

Here’s the aforementioned zombie level in Half-Life 2:

And here’s the aforementioned vehicle section from the game:

Valhalla also switches things up occasionally. One of its regions, for instance – Vinland – forces the player to give up all of their equipment and items and “live off the land,” while searching for their assassination target. Unfortunately, like most things in Valhalla, this area does outstay its welcome, but it’s still a great change of pace. In fact, Valhalla could’ve benefitted greatly from more such unexpected moments.

So, by forcing the player to adapt to a new set of circumstances from biome to biome can be a great way of keeping the player on their toes, and in turn, entertained.

3. Drop the Standard Mission/Quest Structure

Ever since the launch of Rockstar’s Grand Theft Auto 3 back in 2001, many open-world games have been copying its open-world mission structure. It goes something like this: the player talks to a “mission giver,” then immediately goes on to accomplish the mission – usually within a set of very specific parameters (e.g. don’t kill anyone, don’t get spotted, do it in less than X number of minutes, etc.). Failing to meet these parameters usually leads to a fail state, prompting the player to restart. Games like Ghost of Tsushima and Rockstar’s latest titles, like Red Dead Redemption 2, still roughly follow this format.

The Witcher 3 – released in 2015 – provided an alternative. In this game, the player talks to someone to receive a quest, then completes it at their leisure. Such quests are typically more open-ended, in the sense that the player doesn’t have to meet any specific parameters, and sometimes, can even dictate their outcome. These quests are also longer than your standard missions and may overlap with other quests. Assassin’s Creed games have adopted The Witcher 3 approach since the release of Origins in 2017 and haven’t dropped it since (to their benefit, in my opinion).

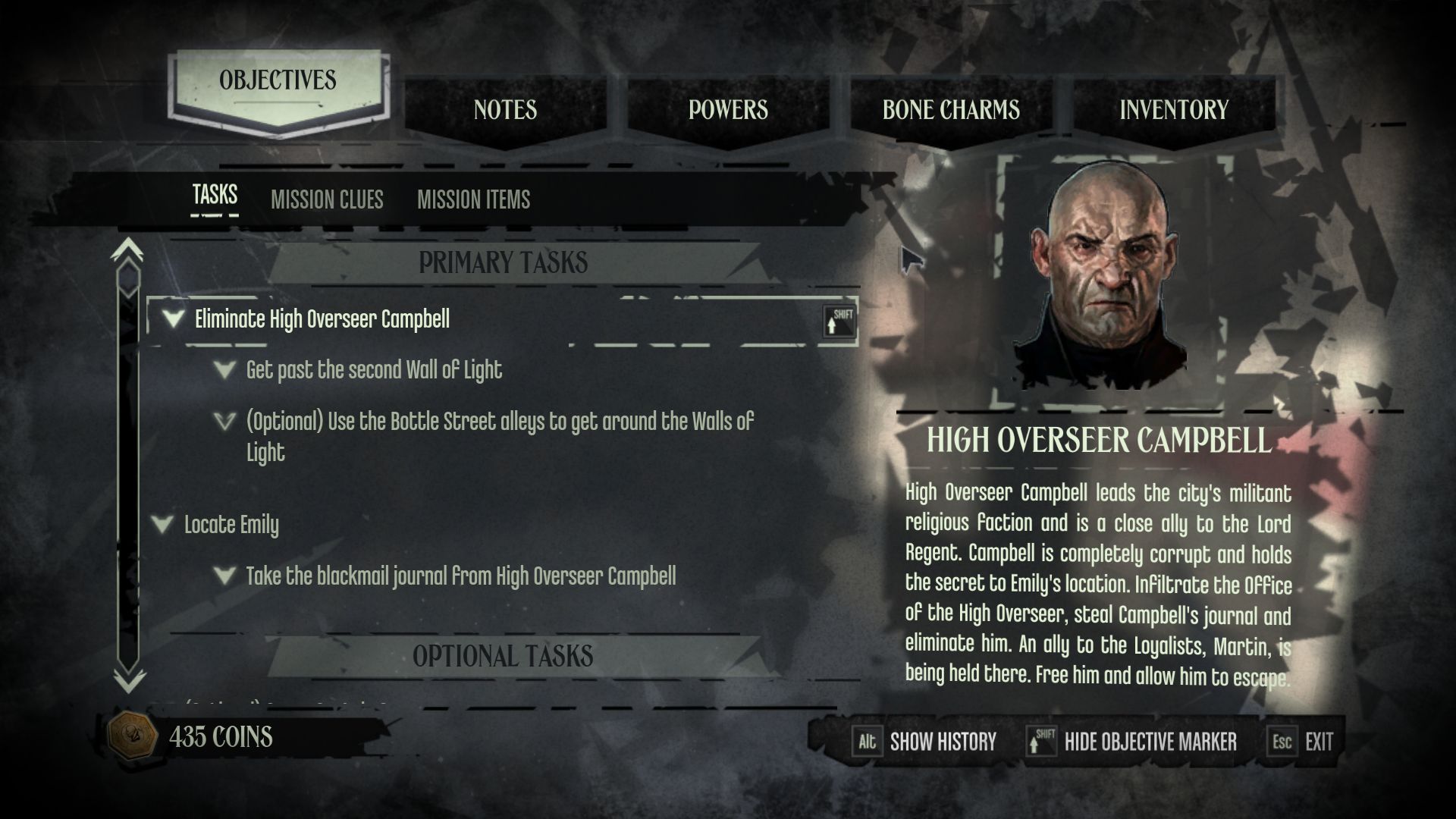

These approaches are not ideal because of the restrictions they impose upon the player, particularly the mission structure in Rockstar’s games. What I suggest is taking what The Witcher 3 does and mixing it with the approach of the immersive sim games like Deus Ex, Dishonored and Prey (the 2017 one), wherein each biome has one or two main quests, and that’s it.

Quest menu in Dishonored.

Like in those games, the quest should be vague and not utilize map markers or other guiding mechanisms – to encourage player exploration and use of the environment. For example, the main quest may be something as simple as finding a particular item within a biome. In this scenario, the player wouldn’t know where to find this item, but they would know that it’s located somewhere within the biome. To find it, they would have to explore the biome as much as possible and interact with everything they find, including NPCs, puzzles, vehicles and so on. In doing so, they would unearth clues that would eventually point them to their destination.

This quest design would allow the player to take full advantage of the open-world structure of the game, since they would have to explore every inch of its map for clues. Side activities would also feel more meaningful and less “fillery,” because many of them would directly contribute to the main objective.

And since the biomes themselves are smaller, the player wouldn’t have to spend too much time traveling around as they look for these clues. Engagement would thus be more frequent and rewarding.

4. Put Gameplay and Story First

What you do in the world, how you do it and what for should be as relevant as the world itself. Ghost of Tsushima, Cyberpunk 2077 and the latest Assassin’s Creed games all have one thing in common – their open worlds are absolutely breathtaking to behold, but what you get to do in them isn’t nearly as engaging. When people praise these games, what they tend to praise the most are their visuals and the world itself.

Here are some examples:

“The game hits a lot of fantastic cinematic highs, and those ultimately lift it above the trappings of its familiar open-world quest design and all the innate weaknesses that come with it–but those imperfections and dull edges are definitely still there.”

— GameSpot on Ghost of Tsushima

“Assassin’s Creed Valhalla is a big, bold, and ridiculously beautiful entry to the series that finally delivers on the much-requested era of the Viking and the messy, political melting pot of England’s Dark Ages. It walks a fine line between historical tourism, top-shelf conspiracy theory, and veiled mysticism against the backdrop of a grounded and focused story.”

— IGN on Assassin’s Creed Valhalla

“Some pieces shine: Night City might be mostly a facade of vanishing non-player-characters, empty storefronts, and senseless traffic patterns, but it’s thoughtfully crafted and enticing to explore. Much of my time in the game has been spent just driving for miles, admiring how naturally a busy commercial hub becomes an imposing corporate center becomes a run-down residential neighborhood becomes abandoned outskirts.”

— Kotaku on Cyberpunk 2077

These may seem cherrypicked, but I assure you, they are not. Go ahead and read the reviews on any latest open-world AAA game and find me one review that DOES NOT praise the game’s visuals over its story and/or gameplay.

My point is that most open-world game developers focus on the world and its visual fidelity above all else. Let’s once again examine Assassin’s Creed Valhalla (sorry). Most of its gameplay systems are borrowed from its predecessors – Origins and Odyssey – particularly the combat system and RPG/loot mechanics. The story is the standard Viking fare you’ve likely already seen in popular TV shows like Vikings and The Last Kingdom, which means there’s little new here, narrative-wise. As such, the most impressive aspect of the game is how Ubisoft has visually recreated the worlds from those two shows and mixed them with the gameplay already developed for Origins and Odyssey (which in turn borrowed it from the likes of Dark Souls and The Witcher 3). That’s great, I suppose, but if you’ve played Odyssey and watched Vikings, then Valhalla won’t seem all that special to you. Stripped of their visuals, Ghost of Tsushima and Cyberpunk 2077 wouldn’t seem all that special either, since they too are rife with overly familiar story tropes and gameplay mechanics.

What I propose going forward is the reverse of the “world-first” approach. Conceive your gameplay loop before everything, then tie it to a story, and finally, tie both to a setting where they will thrive. To find a perfect marriage between gameplay, setting and story, look no further than Doom (yes, the one from 1993). The gameplay premise is a simple one – shoot demons and collect keys across a variety of increasingly complex maps. Story is equally simple – stop those pesky demons from invading Earth and annihilating humanity.

Dooooom!

The best setting for shooting demons, arguably, is hell itself, and that’s where the hero of Doom ultimately ends up heading. But where does he start? A small town on Earth? No, that’s too bloody boring. That’s why he starts in a futuristic research facility on one of Mars’ moons. Why Mars? Because it’s more fun to look at than Earth, that’s why (play Doom 2 to confirm this). However, is Doom’s setting and overall look more important than its gameplay? Decidedly NOT, because the act of shooting demons is so engaging, so persistent that you’ll hardly notice the setting at all – until you get lost in it as you hunt for those annoying keys.

Open-world games should strive for the same level of engagement. The player should never, ever feel as though they are traversing a pointlessly large and empty landscape for a purpose that doesn’t fulfill their gameplay or story desires. They should never lose track of what they are after, and what they do in the world should always be “fun” (the way shooting demons is “fun”). Sometimes, traveling across a desolate landscape is “fun,” but when done too often, it can become boring (like in Valhalla).

Game makers need to become better curators of their content, so they can make their worlds as engaging as possible. In other words, they need to become good storytellers.

In Conclusion… (Or Whatever I Should Put Here)

It’s unlikely anyone will take these suggestions into consideration, but hey – a man can dream! If you have dreams too – particularly about how you want open-world games to evolve – do drop a comment. I’m curious to see your thoughts on this. I’m also very excited to see From Software’s take on the open-world formula in Elden Ring. Those guys rarely disappoint. So, if you want to discuss Elden Ring while you’re here, please do!